Trade in Food

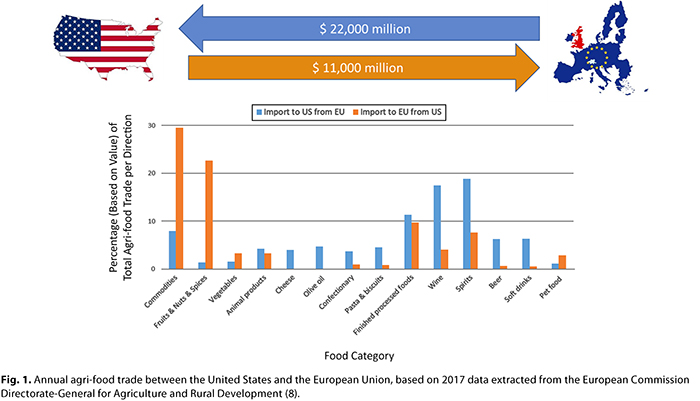

The European Union is the largest trading partner for the United States, and in the case of the food trade, the European Union is the fourth largest export market for the United States (19), whereas the United States is the largest food export market for the European Union (8). As shown in Figure 1, the annual value of food currently traded between the United States and the European Union is US$33 billion (8). There is twice the value of food entering the United States compared with the value of food entering the European Union, and the United States–European Union food trade deficit is growing. Soybeans make up much of the U.S. commodity exports to the European Union, of which a significant proportion enters the animal feed chain or is traded further, whereas the flow of commodities from the European Union into the United States is made up largely of specialty ingredients, such as starches and gums. Fruits, nuts, and spices are particularly important to U.S. exports, whereas the EU trade surplus is largely driven by exports of alcoholic beverages such as wine, cheese, olive oil, confectionary, and pasta. However, of equal importance to both markets is a wide range of other processed finished foods, including products based on cereals. Despite the scale and importance of the food trade between the United States and the European Union, there are fundamental differences between the markets regarding the legal controls in place that determine the acceptability of foods, which causes friction in commerce.

This friction in trade between the United States and the European Union has been brought into focus in discussions concerning the future relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom as it prepares to leave the EU block. On one hand, both countries have been enveloped by a seemingly similar populist agenda; on the other hand, however, the differences in food acceptability have been exposed and are stark. The referendum on EU membership organized by the U.K. establishment was held based on the assumption that the result was certain; however, the populist revolt that drove the electorate was not at all predicted, much like the results of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Although these changes have made both countries keen to develop a new relationship, the United States has made it clear that the United Kingdom needs to reduce or eliminate unjustified restrictions and technical barriers to trade (20) resulting from legacy EU regulations. In contrast, the United Kingdom remains grounded in the EU approach to food management, and there is public sentiment not to reduce controls that protect the perceived “wholesomeness” of foods. Frequently quoted examples of U.S. foods that should not enter the U.K. (or EU) market include a range of genetically modified crops and chlorine-washed chicken and meat from animals treated with hormones (3).

In this article, key differences between regulatory regimes and the points at which there is concurrence and incompatibility are explored. In most cases, both national and multinational companies are aware of regulatory differences that affect their products, and noncompliant trade does not happen. To quantify the impact of regulatory differences, it would be necessary to know which products would be traded and at what scale if there was regulatory harmonization. This calculation would unfortunately be hypothetical at best because it would include variables such as consumer demand. These uncertainties notwithstanding, in order to understand the source and degree of trade friction due to regulation, there is value in examining real data on the official scrutiny taking place in both markets regarding imported products.

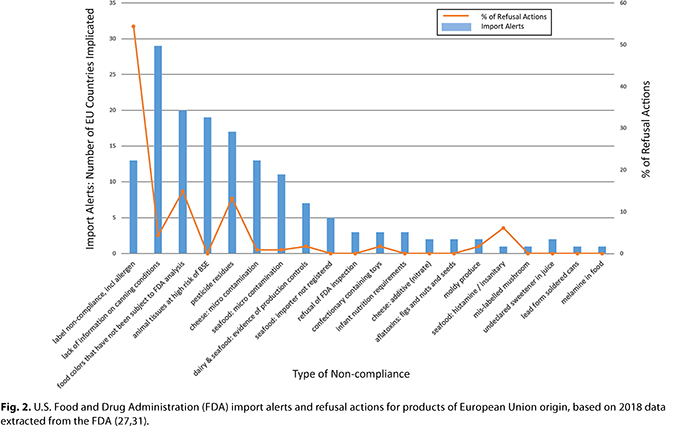

Friction in Trade

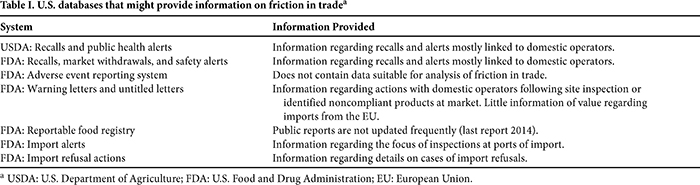

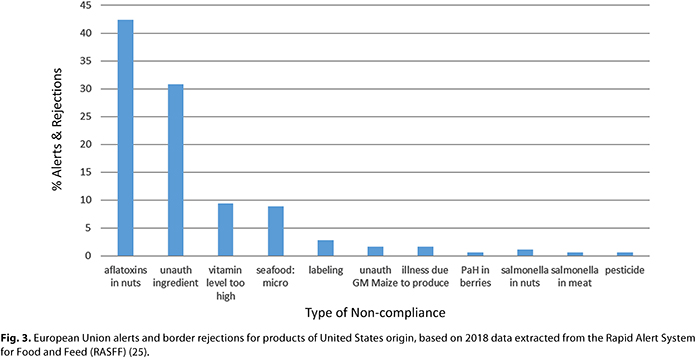

In the United States there are seven systems that may provide insight into what may be considered noncompliant products from the European Union, including those that may be unsafe, A summary of these systems is provided in Table I. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) operates the Recalls, Market Withdrawals, & Safety Alerts system, which contains approximately 2,000 entries/year, while the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) operates a public alert system for meat products. The FDA also operates the Adverse Event Reporting system and the Warning Letters system. The purpose of all these systems is to manage incidents through domestic operators, and it is not possible to systematically access geographic data on the origins of imports. The FDA Reportable Food Registry (RFR) is the portal through which the industry must submit instances of foods that may present health risks; however, the public reports from the system are not updated frequently. Nonetheless, the RFR is used as an input into the Import Alert program, the purpose of which is to increase scrutiny via inspection of products and suppliers when standard checks have identified a potential issue with compliance. The Import Alert system can be compared to the FDA database of Import Refusals. The range of import alerts active in 2018 for foods from the European Union is illustrated in Figure 2. These alerts are indicative both of issues that have been identified through experience at border posts and those that are of concern to the FDA. Also shown in Figure 2 is the percentage of import refusals by type of noncompliance. This data can be compared with the public EU alert system (known as the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed [RASFF]), which lists issues that are perceived to present possible health risks: there are approximately 4,000 different issues identified each year, of which 5% concern foods originating in the United States (24). The reason and scale of alerts for and rejections of U.S. products from the EU market are illustrated in Figure 3. Almost all of the alerts for and rejections of foods in both directions of trade are due to differences in regulatory requirements for labeling, contaminants, and accepted ingredients. Only a small proportion of alerts and rejections are due to clear food safety issues, such as product spoilage.

The predominant issue identified with foods imported into the European Union from the United States is noncompliant concentrations of aflatoxins in nuts. This reflects the importance of trade in nuts, and the difference in regulatory limits for contaminants between these trading blocks. In common with the U.S. system of import alerts, the European Union maintains a list of foods subject to increased inspection. For example, 10% of shipments of pistachios originating from the United States are subject to inspection for mycotoxins (7). The second most important cause of rejections of products originating from the United States is nonauthorized ingredients; in fact, this ranks as the fourth largest single cause for rejection for all products inspected for entrance into the European Union (after aflatoxins in nuts from China, pesticides in produce from Turkey, and Salmonella spp. in meat from Brazil). The usage level of ingredients such as vitamins within foods is also a significant cause for rejection of products at EU borders.

This contrasts with U.S. import alerts for products from the European Union, wherein the issue of whether an ingredient is itself suitable for use in food is not featured. In addition, compliance with use of ingredients within foods is of relatively limited concern (an exception being the use of nitrate in some cheeses). Instead, the main concern with ingredients entering the U.S. market is related to a specific requirement for FDA analysis of synthetic color additives. Another specific compliance issue that is prevalent in U.S. import alerts is the need for production processes to be filed for low-acid canned foods. Logically, however, a significant proportion of FDA import alerts are issued on microbiological controls, hygiene, and the registration and suitability of production locations. Import alerts result in increased holds and inspections, and in some, but not all, cases, import alerts are correlated with data on import refusals. In addition to analysis of synthetic color additives and process data (i.e., provision of the correct paperwork) for low-acid canned foods, common reasons for import refusal include noncompliant labeling, which are driven by the important trade in confectionary products and include issues such as the idiosyncratic requirement to label coconut as an allergen; pesticide residues in olive oil and rice; and spoiled seafood and produce.

The alerts and rejections occurring in both directions of trade reflect differences in the products traded between the partners, as well as differences in regulatory regimes and enforcement priorities. The United States is primarily focused on measures that help ensure the hygiene and microbiological quality of products, in addition to compliance with label requirements and pesticide residues; a limited number of distinct regulatory issues are also prevalent, however. EU actions, on the other hand, are focused predominantly on regulatory compliance with contaminants and acceptability of ingredients.

The Regulatory Landscapes

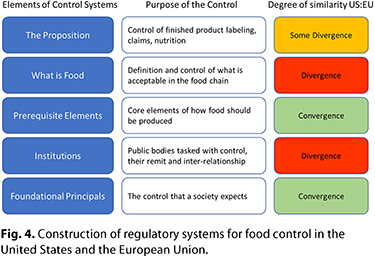

To understand how differences in the food controls enforced by the U.S. and EU regimes create trade friction, it is useful to look at the fundamental elements of public food control systems. The hierarchy of controls within food regulatory systems and the degree of convergence or divergence between the U.S. and EU trading blocks are illustrated in Figure 4.

To understand how differences in the food controls enforced by the U.S. and EU regimes create trade friction, it is useful to look at the fundamental elements of public food control systems. The hierarchy of controls within food regulatory systems and the degree of convergence or divergence between the U.S. and EU trading blocks are illustrated in Figure 4.

At the foundational level, there is convergence. Both societies expect that food is available, affordable, safe, and nutritious. The former (availability and affordability) is met by the adequate functioning of a commercial market, and the latter (safety and nutrition) is controlled principally by food regulation. Food should, of course, also be appealing while meeting future challenges, such as sustainability, and in this respect, the authorities of both trading blocks support innovation.

At the institutional level, however, there is major divergence between the United States and the European Union in the structure of their institutions and the ways in which they deliver on their societal objectives. Notwithstanding the divergence in the structure of institutions, there is some convergence on the core deliverables: the controls that should be in place to ensure food is produced safely. Although there will always be differences in the details of control regimes, convergence can be seen between the EU “farm to fork” hygiene regulations and the recent risk-based prevention standards included in the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) regulations. For example, points of similarity with respect to trade include the registration and control of foreign production sites and prior notification of import. There are some aspects of basic food safety, such as veterinary controls, wherein there has historically been mutual recognition between the regions. Furthermore, there are specific topics for which there is established harmonization, such as agricultural products designated as organic (26).

There is important divergence between the United States and the European Union in the controls for what is considered acceptable in the food chain. There are significant differences in the management of ingredients and their specification and contaminants and residues in finished products. As discussed earlier, this divergence is a cause of friction in current trade, and it is linked to differences in the structure and function of the institutions tasked with food control. It is interesting to view these differences through the lens of history. The EU regulatory culture emerged from the ancient practice of controlling what is acceptable for foods that are traded—for example, standards of identify and purity for cheese, beer, bread, etc. The evolution of regulations began with controlling simple foods at a time when trade was local. In contrast, as a more recently developed country the United States had no established controls on food at a time of industrialization and expanding global trade. It was not until 1906 that the first U.S. federal regulation was enacted after a prolonged campaign by the USDA that led to public outcry over practices that included the use of formaldehyde to extend the shelf life of “fresh” milk. The Pure Food and Drug Act enabled the USDA to seize foods at market that it believed were injurious to health and to test their belief in court. This culture of postmarket control of ingredients has been echoed to some degree in all subsequent regulatory developments in the United States. In contrast, European countries and subsequent European Union have gradually built layers of premarket controls that now cover most aspects of what may be used in foods. In some cases, these controls may have started to lose the link with their original purpose. For example, the alerts in the EU public RASFF system discussed above are intended to be made only after they are judged as a potential health concern. In some cases, however, instead of being based on the safety of the product itself, they are based on regulatory limits not directly linked to safety.

The highest level of these food control systems concerns those regulations that apply to the product as presented to consumers—the fundamentals of labeling of ingredients, nutrition, hazards such as allergens, and shelf life. With regard to this element, there is broad commonality between the trading partners, but notable differences in their regulatory details. This also has an important impact on trade friction. Regulations on claims, such as nutrition and health claims, are particularly divergent. Differences in labeling and sale requirements create friction in trade as well, presumably because an exporting organization is not sufficiently aware of the requirements in the destination market. These issues are easier for ports to control compared with those that require analytical data.

The following discussion will not focus on the topics causing trade friction that could be resolved by better regulatory understanding between trading parties, but rather on the topics that are inherent to products due to regulatory differences between the United States and the European Union. These differences are related to what is considered acceptable in the food chain and the institutions driving those determinations.

Responsibilities of U.S. and EU Regulatory Institutions

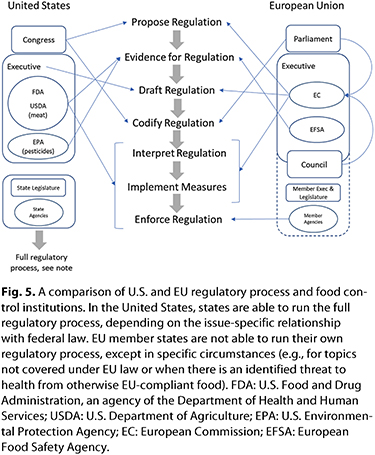

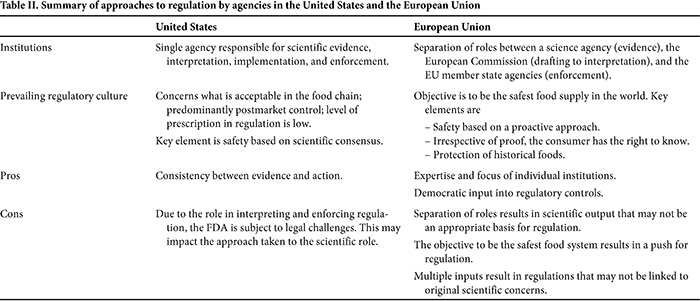

There is a fundamental difference in the responsibilities held by regulatory institutions in the United States and the European Union, as shown in the development process for new regulatory measures illustrated in Figure 5. In the United States there is a single institution responsible for scientific evidence and the interpretation, implementation, and enforcement of regulations. In contrast, in the European Union there is a deliberate separation of roles between science, interpretation, and enforcement. Despite these differences, the resources applied across both regions are similar: both the FDA and the combined EU institutions have budgets of approximately US$300 million for scientific and regulatory activities, excluding enforcement (6,30). In the case of enforcement, the FDA has a budget of approximately US$700 million, and although it is difficult to calculate the cost to the European Union of enforcement due to the number of different agencies involved across the block, an estimation based on the largest members is that the budget is similar to that of the United States. A further similarity is that across all agencies, safety and security of the food supply is considered the highest priority. In this regard there is continual investment of public funds, particularly by the European Union, which has allocated a budget of approximately US$1.5 billion/year (10% of the region’s total research budget) on initiatives to meet the challenges of food safety and security identified in the Food 2030 project (4). As a part of this initiative, the European Union is seeking to both reduce friction in trade, partially through the application of new digital solutions, and to increase oversight of food integrity, which it defines as “ensuring quality and authenticity in the food chain.”

There is a fundamental difference in the responsibilities held by regulatory institutions in the United States and the European Union, as shown in the development process for new regulatory measures illustrated in Figure 5. In the United States there is a single institution responsible for scientific evidence and the interpretation, implementation, and enforcement of regulations. In contrast, in the European Union there is a deliberate separation of roles between science, interpretation, and enforcement. Despite these differences, the resources applied across both regions are similar: both the FDA and the combined EU institutions have budgets of approximately US$300 million for scientific and regulatory activities, excluding enforcement (6,30). In the case of enforcement, the FDA has a budget of approximately US$700 million, and although it is difficult to calculate the cost to the European Union of enforcement due to the number of different agencies involved across the block, an estimation based on the largest members is that the budget is similar to that of the United States. A further similarity is that across all agencies, safety and security of the food supply is considered the highest priority. In this regard there is continual investment of public funds, particularly by the European Union, which has allocated a budget of approximately US$1.5 billion/year (10% of the region’s total research budget) on initiatives to meet the challenges of food safety and security identified in the Food 2030 project (4). As a part of this initiative, the European Union is seeking to both reduce friction in trade, partially through the application of new digital solutions, and to increase oversight of food integrity, which it defines as “ensuring quality and authenticity in the food chain.”

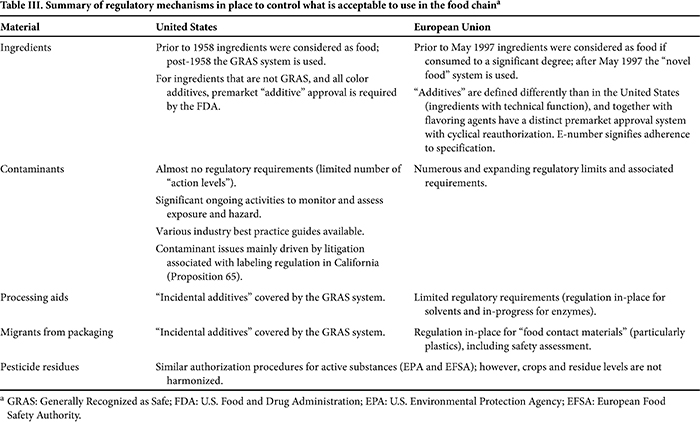

A summary of the approaches to regulation applied by food control agencies to determine what is acceptable to use in foods is provided in Table II, and a summary of how this is translated into regulatory mechanisms is provided in Table III. There are two fundamental differences between the U.S. and EU regimes that may create barriers to trade. First, in the case of most food ingredients in the U.S. market there is no legal requirement for approval by authorities. This is in contrast to the European Union, where premarket authorization dominates and, in the case of additives and pesticides, there is a rolling rereview. Second, the European Union operates a continuous program of contaminant assessment that feeds into a process to draft regulatory measures; the motivation for the program is to continuously reduce contaminants across the food chain. This is in contrast to the United States, where contaminants are not generally subject to regulation and instead there is a process of monitoring and assessment with nonbinding guidance provided to food businesses. However, notwithstanding the management of food contaminants at the federal level, an important factor driving regulatory issues concerning contaminants in the United States is litigation associated with the requirement for label warnings regarding cancer and reproductive effects under California’s Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986 (18) (otherwise known as Proposition 65). This is a unique regulatory instrument, wherein citizens and organizations are rewarded a portion of civil penalties for bringing litigation against businesses. It has the effect of increasing the cost of doing business in the internal U.S. market, with unclear benefits for consumer protection. The impact of Proposition 65 on international trade between the United States and European Union is not possible to quantify, but is probably limited based on the predominant types of products imported into the United States and the focus of current litigation.

The U.S. GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) system provides a regulatory environment wherein food businesses, with the help of suitably qualified experts, are responsible for managing the assessment of whether their ingredients, including new ingredients, are safe and, therefore, suitable for their intended use. A food business can manage the determination of whether an ingredient is “generally recognized, among qualified experts, as having been adequately shown to be safe under the conditions of intended use” (32). The FDA has no right of premarket review, and its role is primarily postmarket enforcement. However, in situations where a food business operator voluntarily discloses their assessment to the FDA, the agency will review the data and issue a letter stating whether there are no questions (i.e., no objection) or insufficient basis to determine the substance is GRAS (i.e., objection). Although GRAS as a regulatory system was created in 1958, the current system, which includes voluntary notification, was initiated in 1997 as a pilot program, with a final rule issued in 2016 (28). The final rule provides a number of clarifications, including information on the structure of dossiers written to support GRAS determinations based on common knowledge (i.e., published data) by a group of experts. A stakeholder group that includes the food industry is currently working together to build on this clarification by providing a more detailed standard on best practices in the conduct of ingredient safety assessments (known as GRAS-PAS [13]).

The GRAS system has attracted controversy since its inception, in particular the quality of assessments that have not been disclosed to the FDA (i.e., “self-GRAS” assessments). The quantity of these and importance to both the food industry and food supply are open to question; however, it is likely that the bulk of self-GRAS assessments concern minor modifications to known food ingredients. The effectiveness of the GRAS system is indicated by the fact that in the 10 years preceding publication of the final rule in 2016 the FDA issued only 59 warning letters related to GRAS ingredients (14). Many of the warning letters were related to enforcement actions to remove specific ingredients from the food chain (e.g., ephedra, melatonin) or the suitability of ingredients for specific food categories (e.g., caffeine in alcoholic beverages). The U.S. market benefits from the flexibility of the decentralized management of ingredients, but there are legitimate concerns about the transparency and quality of assessments. This is in contrast with the centralized and, therefore, less flexible management of ingredients in the EU market, which is perceived to be relatively transparent and rigorous. The contrast between the markets is evidenced by the import alerts and refusals for ingredients that are considered by the European Union as noncompliant “novel foods” or unapproved additives (Fig. 3).

There are both advantages and disadvantages to having institutions with defined or combined roles. An example of the conflict affecting the FDA resulting from its combined role is the recent action it took to no longer authorize six flavoring agents due to a legal challenge related to their safety, despite the rule making it clear that the ingredients are safe (29). The ingredients in question were part of a grandfathered list of flavoring agents in the market prior to the 1958 amendment of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 that created the GRAS system. The legal challenge was based on a clause in the amendment that provided an unqualified restriction for additives shown to induce cancer in animal tests. This is irrespective of more recent understanding or the relevance of the animal tests to human health. Some of the implicated flavoring agents have been assessed and are permitted in foods within the European Union. These idiosyncratic legal issues create an impediment to trade. However, the potential for impediments to transatlantic trade resulting from the U.S. model are perhaps insignificant compared to the challenges resulting from the EU model.

As shown in Figure 3, the greatest single reason for rejection at the EU border is noncompliance with contaminant limits. It is a common misunderstanding that rejection by the European Union is due to the application of what is known as the “precautionary principal.” There are various definitions of what this means, but it generally refers to actions taken to protect health even if cause-and-effect relationships have not been fully established scientifically. The reality of what drives the EU approach to chemical food safety is more complex. The region utilizes a proactive approach to contaminants under a political agenda to maintain the safest food chain in the world. As the European Union actively seeks to align its approach with the wider international market (9), the direction of global food safety systems is trending toward increased polarization between the U.S. and EU models. Despite the logic underlying the separation of roles between the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the European Commission (EC), and the EU member states, which enables the independent focus and expertise of those institutions, the model can be conflicted and produce food controls that have unclear value to consumer protection, while raising barriers to both internal and international trade. At a recent meeting of the Codex Committee on Contaminants (2), in which international trade standards are developed, the global community was repeatedly frustrated in its attempts to establish contaminant limits based on safety for important food commodities due to the EU block’s refusal to accept such limits based on its preexisting regulations. This behavior not only results in friction between trading blocks but is an impediment to the development of impoverished nations who are seeking to export agricultural commodities.

An illustrative example of the difficulties inherent with the EU model is a contaminant known as 3-MCPD (3-monochloroproanediol), which is produced during the refining of vegetable oils. Oils such as palm oil are important for many food categories, including cereal-based foods such as biscuits. In 2016 EFSA published a safety opinion (21). The opinion was revised in 2018 (22) following concern from the scientific community, including from a separate committee within EFSA itself, that the mathematics underlying the opinion could be improved. The original opinion identified a safety concern for a range of young consumers, whereas the revised opinion stated concern principally for a specific class of infants fed substitute milk formula. In this work, the determination of whether there is a safety concern rests on minor differences in the calculated values, which in the context of the uncertainty and precautions built into the calculation will quite possibly be viewed by future generations as false precision. In this case, although the risk to health was identified principally for infants, a class of consumer for which individual regulations are commonly applied, the EC has pushed ahead with drafting limits for all oils used in all products. In addition to this lack of coherence concerning the safety status of 3-MCPD, at the time of writing, the proposed limits are based on the lowest levels that can be technically achieved. This is an approach the EU regulations themselves state are appropriate in the case of certain situations, such as when a contaminant is a genotoxic carcinogen (5), which 3-MCPD is not.

Therefore, in the European Union the situation with regard to contaminants is that the regulatory institutions are at times amplifying the value judgments other institutions are making, such that the end result may be disproportionate to the objective of proactively protecting consumer health. Instead of providing estimates of actual risk set in the context of the surrounding uncertainty, EFSA often appears to interpret its role as seeking to pass a yes or no judgment on whether there is a risk to health. This is despite the reliance on toxicological data that may be of uncertain relevance to humans, the complexity of the calculation, and the degree of correlation to the reality encountered by consumers. This judgment is then passed on to the EC, where regulation invariably is drafted in cases where a risk to health has been pronounced. The regulation then comes under political influence, which can further skew the outcome such that the benefit to consumer protection could be questioned. This is in contrast to the approach of the FDA to contaminants, wherein there is close monitoring of developments, advice given to food operators, and little regulatory activity.

Even in cases where EFSA provides an opinion that does not identify a concern, the result may still be regulatory action. A further example of how organizational and cultural differences lead to different regulatory requirements that may impact trade, is the management of the “Southampton colors.” In 2007 a study was published on the effects of mixtures of synthetic food color additives on child behavior, in particular attention deficit and hyperactivity (17). This study was part of the ongoing debate on whether food additives can impact child behavior. Both the FDA and EFSA concluded that the study did not substantiate a link between the color additives that were tested and behavioral effects (16,23), and on this basis, the FDA did not take regulatory action (1). However, the EC implemented a regulation that requires a food product that contains one or more of the color additives to be labeled as “may have an adverse effect on activity and attention in children” (11). The EC implemented this regulation because even in cases where the science agency does not communicate a clear concern, other inputs are considered via a process of negotiation on a common position with member states. In some cases, labeling requirements may be deliberately divorced from the original safety concern if it is perceived that European consumers desire information on the subject, such is the case for recent labeling requirements on nanomaterials (12). It is clear, therefore, that compared to the United States, the European Union maintains a dynamic regulatory environment as it pertains to either well-defined, emerging, or perceived food safety issues.

Future Prospects

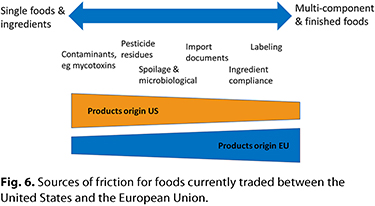

The U.S. and EU models for food control are fundamentally similar, with a limited number of notable differences in how ingredients and contaminants are managed, and this is driven by organizational and cultural differences. As the data demonstrate, these differences underlie much of the friction identified in current trade. Types of products by trading block and associated noncompliance issues identified are illustrated in Figure 6. At the global level, there is likely to be increasing polarization as developing countries move toward either the U.S. or EU model. Notable impediments to trade arise due to subversion of the parts of the control systems where regional differences exist, either due to legal challenges, as per the U.S. model, or to loss of coherence in logic, as within the EU model. A commonality underlying this subversion is the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The majority of NGOs provide great service in championing public causes, but some serve their own purposes irrespective of public benefit. In recent years these organizations have demonstrated dexterity in interfacing with the food control systems of both the United States and the European Union, and this has been partly aided by the laudable movement toward increased transparency in these systems. Particularly in the European Union, where political considerations are part of operational food control (via the EC), there is substantial influence. An example is the limited reregistration and possible prohibition in some member states of glyphosate, an herbicide that all food control agencies unanimously agree is safe for its intended uses, including its residual presence in foods such as cereals. There may come a point at which the momentum toward increased transparency impacts not just the political elements within risk-management decisions, but also the ability of expert agencies to conduct their work. Currently, public consultations are held on the draft outputs of EFSA, and this is a valuable process. However, following the debates on glyphosate, the EC proposed that in the future all data (studies and documents) submitted to EFSA for its review should also be open to public scrutiny. At the time of writing, this measure had been adopted by the European Parliament (10). The presumed benefits of this transparency are clear: the ability to ensure the body of available input data is available so risk assessment can be based on the full weight of evidence. However, it does not appear that the range of potential impacts have been considered—it might be that without careful management, the cacophony of input, including third-party assessments and associated media noise, could impair the independence of EFSA and undermine the separation of roles between EFSA and the EC. The fact that the initiative arose at the behest of the EC from the glyphosate debate, upon which the scientific evidence is abundant and available, indicates that it is driven by political considerations linked to transparency as opposed to support for scientific rigor. It is noteworthy that the initiative includes a proposal for EFSA to initiate its own studies, which presumably would help ensure that critical scientific questions are addressed, thus reducing uncertainty in outputs. It will be interesting to see how this develops, and perhaps, in the future compare to U.S. initiatives such as the CLARITY-BPA research program (15), in which a large amount core work by government agencies (National Institute of Environmental Sciences [NIEHS], National Toxicology Program [NTP], and FDA) was complemented by an array of hypothesis-based academic research.

The U.S. and EU models for food control are fundamentally similar, with a limited number of notable differences in how ingredients and contaminants are managed, and this is driven by organizational and cultural differences. As the data demonstrate, these differences underlie much of the friction identified in current trade. Types of products by trading block and associated noncompliance issues identified are illustrated in Figure 6. At the global level, there is likely to be increasing polarization as developing countries move toward either the U.S. or EU model. Notable impediments to trade arise due to subversion of the parts of the control systems where regional differences exist, either due to legal challenges, as per the U.S. model, or to loss of coherence in logic, as within the EU model. A commonality underlying this subversion is the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The majority of NGOs provide great service in championing public causes, but some serve their own purposes irrespective of public benefit. In recent years these organizations have demonstrated dexterity in interfacing with the food control systems of both the United States and the European Union, and this has been partly aided by the laudable movement toward increased transparency in these systems. Particularly in the European Union, where political considerations are part of operational food control (via the EC), there is substantial influence. An example is the limited reregistration and possible prohibition in some member states of glyphosate, an herbicide that all food control agencies unanimously agree is safe for its intended uses, including its residual presence in foods such as cereals. There may come a point at which the momentum toward increased transparency impacts not just the political elements within risk-management decisions, but also the ability of expert agencies to conduct their work. Currently, public consultations are held on the draft outputs of EFSA, and this is a valuable process. However, following the debates on glyphosate, the EC proposed that in the future all data (studies and documents) submitted to EFSA for its review should also be open to public scrutiny. At the time of writing, this measure had been adopted by the European Parliament (10). The presumed benefits of this transparency are clear: the ability to ensure the body of available input data is available so risk assessment can be based on the full weight of evidence. However, it does not appear that the range of potential impacts have been considered—it might be that without careful management, the cacophony of input, including third-party assessments and associated media noise, could impair the independence of EFSA and undermine the separation of roles between EFSA and the EC. The fact that the initiative arose at the behest of the EC from the glyphosate debate, upon which the scientific evidence is abundant and available, indicates that it is driven by political considerations linked to transparency as opposed to support for scientific rigor. It is noteworthy that the initiative includes a proposal for EFSA to initiate its own studies, which presumably would help ensure that critical scientific questions are addressed, thus reducing uncertainty in outputs. It will be interesting to see how this develops, and perhaps, in the future compare to U.S. initiatives such as the CLARITY-BPA research program (15), in which a large amount core work by government agencies (National Institute of Environmental Sciences [NIEHS], National Toxicology Program [NTP], and FDA) was complemented by an array of hypothesis-based academic research.

In a landscape in which partisan pressure impacts food control systems through political processes, legitimate questions are raised about the difference between public protection and public interest. As discussed, the European Union has a predilection for mandatory labeling when it is perceived that the consumer would like information. Some of these topics may originally be rooted in a safety concern, such as nanomaterials and synthetic color additives, but as the control agencies already manage the safety of these issues, there is a disconnect between the message being given to consumers through the labeling (i.e., “this is labeled to make you aware of the concern”) and the actual risk to health. It could be proposed that by behaving in this way, the European Union is not bolstering public trust in the food chain and its control institutions, which it is seeking to build. It is likely that in the future this contradiction will not change.

Major sources of trade friction that are likely to remain as such include the required detail of labels on finished foods and the underlying differences in the control of food ingredients and contaminants. There are forces pushing toward both divergence and convergence. For example, the ongoing activity of the European Union to assess and control mycotoxins, including increasing the granularity of requirements for cereals compared with the United States, where there are fewer legal controls on contaminants, runs counter to efforts toward convergence in other areas, such as the work of groups like the International Agri-Food Network (https://emergingag.com/the-international-agri-food-network) to harmonize international requirements for pesticides, including through greater recognition of Codex standards.

Conclusions

This article provides a snapshot of the non-tariff barriers to trade created by regulatory differences between the United States and the European Union. The cultural approach to food safety and societal expectations placed on both trading partners are unlikely to change rapidly. However, regulatory compliance is all about the details, and the details of food regulation are dynamic; factors subject to change include the products traded and emerging health and nutrition concerns. Both food businesses and control agencies need experienced regulatory professionals who understand the limiting details and their impact. Furthermore, to meet the societal objectives of an available, affordable, safe, and nutritious food supply, it is necessary to understand how science plays across the control mechanisms to help in the process of creating controls that are logical and effective. Although there are important initiatives underway to harmonize specific aspects of food control, the trajectory remains on a path toward increased divergence, not just between the United States and the European Union, but also globally. In many cases such divergence may not provide real benefits to consumer protection and may negatively impact the ability to meet basic needs for an available and affordable food supply. One hope for the future is that control mechanisms will put greater emphasis on the prioritization and scaling of health concerns, perhaps through the analysis of benefits against risks in the food chain, such that regulatory measures will be as proportionate as possible. Proportionate and fact-based measures are less likely to result in large differences between regulatory regimes and may help encourage harmonization, reducing unnecessary trade friction.

Neil Buck is corporate toxicologist for the global food company General Mills Inc. At General Mills he spends much of his time on the innovation of products and production processes and on the technical aspects of regulatory affairs. He has a particular interest in consumer protection through evidence-based regulation. After started his working life in the food industry, Neil returned to university to obtain an M.S. degree in toxicology and a Ph.D. degree in food additive safety. He has subsequently spent more than 15 years in industry as both a toxicologist and a regulatory professional. Neil is a member of a number of collaborative groups and participates in the technical committees of Food Drink Europe, the U.S. Grocery Manufacturers Association, and both ILSI Europe and North America. LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/neil-buck-812734a

Neil Buck is corporate toxicologist for the global food company General Mills Inc. At General Mills he spends much of his time on the innovation of products and production processes and on the technical aspects of regulatory affairs. He has a particular interest in consumer protection through evidence-based regulation. After started his working life in the food industry, Neil returned to university to obtain an M.S. degree in toxicology and a Ph.D. degree in food additive safety. He has subsequently spent more than 15 years in industry as both a toxicologist and a regulatory professional. Neil is a member of a number of collaborative groups and participates in the technical committees of Food Drink Europe, the U.S. Grocery Manufacturers Association, and both ILSI Europe and North America. LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/neil-buck-812734a